My father, the birder, is often excited to share his sightings with me — especially so this summer when he got back from a long-planned trip to South Africa. 153 species! I love how he finds joy and peace by connecting with the world through observing birds, interacting with fellow birders, and telling tales of his birding adventures. In so many wonderful ways, Dad’s daily routines and way of life are linked to nature and the birds he loves.

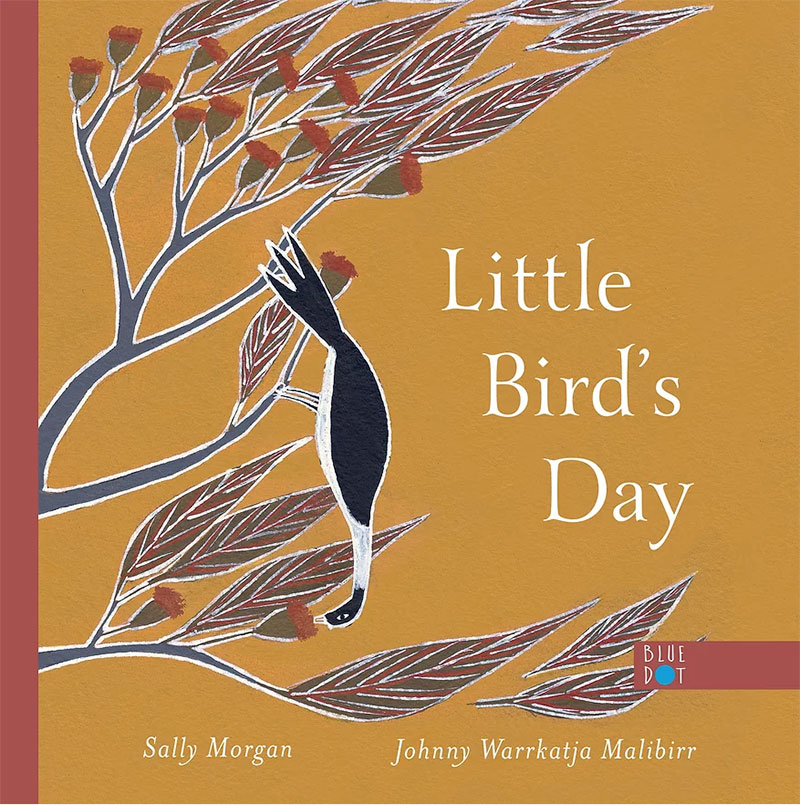

I got that same sense of connection when I read Little Bird’s Day by Sally Morgan; illustrated by Johnny Warrkatja Malibirr. You can feel your energy rising as Little Bird moves through the day interacting with elements of nature. And then you get peace and contentment as Little Bird settles down for the night to rest, the sky darkens, and the world quiets.

It is a delight to have Sally Morgan visit Book Life and help us think more about our connections to the natural world. Sally is an award-winning Australian Aboriginal author and artist and the director at the Centre for Indigenous History and the Arts at the University of Western Australia. In addition to her widely acclaimed first book, My Place, an autobiography, Sally has written a number of picture books, including titles she has written in collaboration with her children.

August 24, 2022

Sharing the World: From Birdsong to Your Song! by Sally Morgan

There are hundreds of Indigenous nations in Australia; my family belongs to the Palyku people of the eastern Pilbara, in the northwest part of Western Australia. For Indigenous peoples, birds are often seen as messengers. This is because birds can bring news, or come to give you a warning or tell you something is going to happen. When I was young, my grandmother would wake me early to show me something special in the garden. Sometimes it was a bobtail goanna making its way through our yard, but often it was a bird, or birds, flying in and out or singing. Magpies, who have beautiful morning and evening songs, were special visitors.

The suburb where we lived was close to large stretches of land filled with trees, several creeks that meandered out from the Canning River, and wildlife. I spent a lot of time enjoying the trees, the wildflowers when they bloomed, watching the animals, and listening to the birds.

As a child, I learned that the world speaks to us, but to hear clearly, you must listen deeply, be sensitive and observant, recognize the signs being offered, and be comfortable with silence. My story Little Bird’s Day comes from childhood experiences that gave me a deep feeling of belonging to the natural world.

I’d love it if your students could interact with the natural world in a direct, intentional way, observe more closely the life around them, and imagine what conversation they might have

with a bird.

Prepare

Discuss in small groups or as a class what species of birds live in your area. Did you see or hear any on your way to class that day? What do they look like? What do they sound like? Do a little research or just use your memory and best guesses.

Where I come from in Australia, I can find not just magpies, which I mentioned earlier, but galahs, cockatoos, willy wagtails, and many other birds.

Little Bird, in my book, is a djulwadak, or a silver-crowned friarbird. These birds have soft-gray feathers and a wonderfully curious “horn” on their long, pointy black bills. They live in the northern parts of Australia, in subtropical and tropical forests, where the illustrator of Little Bird’s Day, Johnny Warrkatja Malibirr, is from. Johnny is a Yolŋu man from the Ganalbingu clan.

The First Nations peoples of the land where you live will have their own special names and stories for the birds in your area, and you might like to learn about this.

Gather

Collect paper, pens, markers, anything you like to help you remember what the birds tell you. You may do so in story, song, poem, or drawing to express what you hear!

Go!

Now, go outside. Maybe set a healthy amount of time that you must stay outside. This isn’t an exercise in which you pop out, say, “I don’t see or hear anything, oh well,” and then come back inside. If you sit still or walk quietly for at least fifteen minutes, you might begin to notice things you haven’t noticed before, and this will help you to learn about the world — help you listen — and to write your own story.